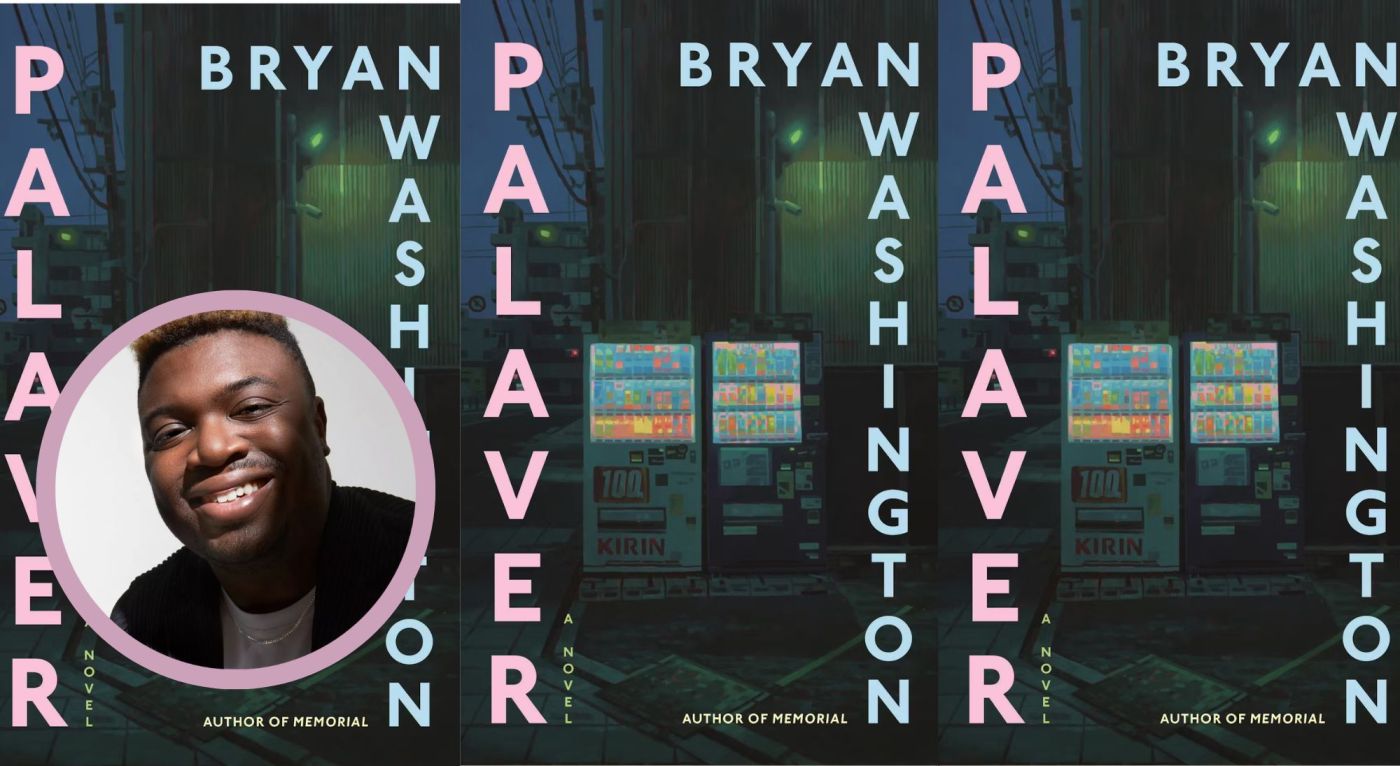

Like his previous two novels and short stories, Bryan Washington’s fourth book, “Palaver,” is set in Houston, where he’s from, and/or Japan, where he now lives. But in “Palaver,” which was nominated for a National Book Award, Washington takes a new tack, stepping back to write from an observant third person. In the novel, a mother, living in Houston, suddenly picks up and flies to Tokyo to check on her son, from whom she is emotionally estranged. The son had been mistreated at home for being gay by his older brother and his parents, even though his mother had grown up in Jamaica with a gay older brother with whom she was incredibly close. SEE ALSO: Like books? Get our free Book Pages newsletter about bestsellers, authors and more The characters are not named the author says using “mother” and “son” throughout creates an “emotional shorthand between the reader and the text “. that felt more interesting to me than ascribing a name to either of them” but we grow intimate with each one as we see their tentative encounters and tenuous connections from both perspectives. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Q. The book shifts perspectives from the son to the mother, and the reader may shift sympathies as it happens. Was that something that you set out to do, or did you just want to see the story from both of their worlds? It began as the latter, but I ultimately edited it toward the former. If I’m writing about a relationship, it’s not particularly interesting for me if the reader steps away and says, “Brian thinks that this character was right, and he showed us why.” What’s more interesting, and more challenging for me structurally, is to give as many different angles from the parties involved as possible, so that the reader is privy to this range of experiences. The works that I’m really taken by, I don’t feel the heavy hand of the author, of the filmmaker, or the musician. So I may guide the narrative one way or another, but it’s ideal for me if a reader is able to find their own sense of what happened, and why it happened, who these characters are, and where they ended up with minimal interference from me. The catch being, of course, that I’m molding all of this. Q. But there’s a moment where the son says, “They lock up people for hitting dogs, let alone what you did to me,” and while we don’t see the violence, that’s pretty damning. And in a later scene, the mother sneers at the son, “That’s how a toddler speaks . not a man.” So did you worry about tilting the playing field? That’s not really something that I’m worried about either, because I was concerned with trying to show the complexity of people as they work toward coming together. This took about five years to write, the longest that I’ve worked on something, because I had to learn who these characters were and what they wanted exactly. I wasn’t really sure until the third year about how they would respond to duress or to conflict. A moment like the one you described, that is not something that would have been possible for me to see in the first year of writing, because I did not know these characters well enough. Q. Did it take you that long because you were writing a third-person observational narrative instead of a first-person immersive one? Third person is not something that I entered this book particularly comfortable with; I don’t know that I can say that I’m comfortable with it now, but I know that it’s something that I can do. I was at least astute enough to realize at the beginning that the first person wouldn’t be compatible with what I wanted to do. I did not want to write a narrative in which a son is dealing with a challenging relationship with his mother or a mother is dealing with her challenging son. What was interesting to me was whether or not reconciliation is possible with a person after challenging experiences, and what it can look like to relearn someone or to navigate and find a middle ground for how to know someone that you thought that you knew. What concessions does someone make? What is not acceptable? And how does that impact the relationship insofar as there can be one going forward?. So I had to find the third person and distance from that to approach those questions in a way that made sense. Q. I read you wrote first-person material not for the book but just to understand the characters better. Reaching that distance in the third person was, for me, just really difficult, so I had to utilize different POVs and different narratives to have a sense of what an emotional beat looked like. Only then was I able to identify that emotional beat from that work and apply it to “Palaver” in this POV that was a little trickier to navigate. Because I was able to glean more insight, it modified how characters may have reacted or the volume or the degree of a response that a character gave. Q. Do you think the mother learns to see and appreciate the son’s self-discovery and community eventually, even though she never expresses it well? I think that by the end the mother has a sense of what she doesn’t understand about the son and what she hasn’t understood about the son. But quite intentionally, it’s just the beginning of her ability to understand the different things that the son has navigated and that he may be feeling and how they differ from her sense of who this person was or is or should be. The journey toward that realization, for both characters, was more interesting to me than just illustrating the epiphany itself for the audience. I wasn’t sure if that could be accomplished in narrative, so it felt like a challenge. Q. Your most recent short story in the New Yorker, “Voyagers,” features a gay expat living in Japan and a woman living in Texas. Yet those familiar locations are in the rear-view mirror as we follow them on a road trip. Was that a conscious choice? I wanted to write a road trip narrative, but also it’s fascinating to me what happens when I apply the things I learned writing about Houston, Tokyo and Osaka to writing about other places and I’m getting more comfortable with that. The story was attempting to see if I could do that. Q. You’ve said you’re not a particularly optimistic person, yet your characters move from isolation to engagement and community. Is that something you think about for yourself? It was a conscious decision. I write towards optimism, knowing that it is not something that comes particularly naturally to me, so it is very much like a “Fake it till you make it” thing. If I continue to at least attempt to walk the path of optimism, then I’ll look up and I’ll be on this trail, regardless of whether or not I feel I should be there.

https://www.sgvtribune.com/2025/11/25/how-bryan-washington-spent-years-finding-a-new-way-to-write-palaver/

How Bryan Washington spent years finding a new way to write ‘Palaver’