Archaeologists have identified traces of two toxic plant alkaloids, buphanidrine and epibuphanisine, on artifacts from Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. These artifacts, known as backed microliths, were excavated from deposits dated to about 60,000 years ago, placing the use of poisoned weapons deep into the Late Pleistocene.

“This is the oldest direct evidence that humans used arrow poison,” said Professor Marlize Lombard of the University of Johannesburg. “It shows that our ancestors in southern Africa not only invented the bow and arrow much earlier than previously thought, but also understood how to use nature’s chemistry to increase hunting efficiency.”

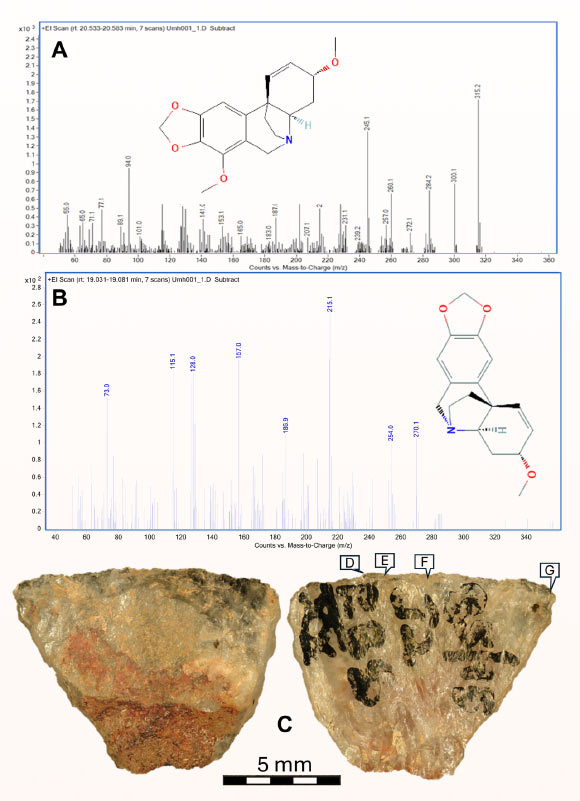

Professor Lombard and colleagues analyzed residues on 10 quartz microliths using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. They identified the two toxic plant alkaloids—buphanidrine and epibuphanisine—on five of the artifacts. These compounds originate exclusively from the plant family Amaryllidaceae, indigenous to southern Africa. The most likely source is a species called *Boophone disticha*, which has been historically associated with arrow poisons.

The residue patterns indicate that the Umhlatuzana microliths were hafted transversely and used as arrow tips. On some artifacts, the poison residue was macroscopically visible along the dorsal backed portion, suggesting that toxic compounds were mixed into an adhesive used to fix the stone point to the arrow shaft. Microscopic impact scars and striations on the edges were consistent with their use as transversely hafted arrow tips.

To confirm their findings, the researchers compared the ancient residues with poisons extracted from arrowheads collected in South Africa during the 18th century. “Finding traces of the same poison on both prehistoric and historical arrowheads was crucial,” said Professor Sven Isaksson of Stockholm University. “By carefully studying the chemical structure of the substances, we were able to determine that these particular substances are stable enough to survive this long in the ground.”

This discovery pushes direct evidence for poisoned weapons much further back in time. Prior to this work, the earliest confirmed use of poison for arrows dated to the mid-Holocene, several thousand years ago. However, the Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter clearly documents such technology at least 60,000 years ago.

According to the authors, poisoned arrows were not designed to kill instantly but instead relied on toxins that weakened animals over time, allowing hunters to track prey over long distances. “Using arrow poison requires planning, patience and an understanding of cause and effect,” said Professor Anders Högberg of Linnaeus University. “It is a clear sign of advanced thinking in early humans.”

The discovery is detailed in a paper published on January 7 in the journal *Science Advances*.

—

**Reference:**

Sven Isaksson et al. (2026). Direct evidence for poison use on microlithic arrowheads in Southern Africa at 60,000 years ago. *Science Advances*, 12(2). doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adz3281

https://www.sci.news/archaeology/pleistocene-poisoned-arrowheads-14470.html